I need you

In May of 2000, my mother, the greatest educator I've ever known, fell into a coma. Rushing back from an education conference in Kentucky, I joined her hospital bedside and remained there every minute that I could. It was unclear whether she'd open her eyes again, but I strove to connect with her as if she would. I relied on every sense I could engage, enveloping the room with the music she loved, letting a cup of fresh Dunkin' Donuts coffee sit with its lid off, holding her hand, and telling her stories, such as that of my encounter with the guy in Harvard Square who was wearing tie-dyed pants and yelling angrily at a pigeon. For days she was unresponsive, yet I kept that vigil. And then, quietly, one afternoon, she awoke.

Those beautiful brown eyes met mine, and I experienced gratitude like never before. She was unable to speak and too weak to write, but her eyes made it clear that she had a lot to say. At that point, her hospital room was full; doctors, nurses, family, and friends had gathered around. I saw in her eyes confusion, fear, love, and frustration all at once. She wanted to ask questions, relay what she was experiencing, ask for help, and yet she couldn't. Until she locked eyes with me, held up one hand, and began to sign.

When I was young, my mom had taught me the sign language alphabet. No one close to us was deaf, but my mom always stressed the value and beauty of communication in all its forms. And so, together, we learned each letter, and practiced sharing messages in public when we were out of earshot or unable to talk. I always found it cool to have a special means of "talking," but I couldn't have imagined its significance one day.

In a moment, I became her voice. She spelled out each word, and I shared it with the room. She'd nod with relief once her message was received and smiled bigger each time she successfully expressed herself. I was literally giddy, and the moment she spelled out "g-u-m," I ran to the gift shop and bought every flavor they had in stock. She just shook her head and giggled.

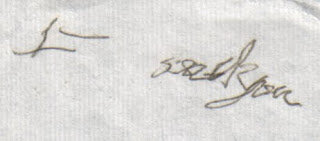

Her health wavered over the subsequent weeks. There were highs and lows, but it was three words that she scribbled on a piece of paper that profoundly impacted me. With a weak hand resulting in a slightly lopsided "n," she wrote "I need you." I haven't been the same person since.

This person who initially showed no response, who couldn't demonstrate to me what she could or couldn't understand, who was afraid and upset with her circumstances, ultimately found her method of connecting. She let me know, in her own way, that my efforts were not wasted. If I hadn't been paying attention, I might have missed it.

What a powerful lesson this experience has offered as an educator. And I'm not one bit surprised. After all, my mom had for years taught children, adolescents, and even adults in prison. She had raised two teenagers, bombarding us with "I love you" no matter how much eye rolling or sighing ensued. It mattered not whether our response was immediate, appreciative, or clear. She sought to connect with her children and learners, whatever it took.

I can only imagine what beauty would transpire were my mom able to teach in a classroom of today, with diverse methods for communicating, sharing, and demonstrating understanding. I would be in awe, I would be humbled, and I'd be taking notes furiously in an attempt to pass onto my own students a portion of her gift.

My mom passed away ten years ago this past Sunday. And yet I find myself less saddled with grief and more inspired to continue learning from her. I will continue to attempt to connect with each of my students, even in the face of unresponsiveness. I will maintain hope. I will celebrate each success. And I will pay careful attention just in case I discover that a student, in her own way, has shown that she needs me.